The Network includes artists and academics from India (BraveSpaces Creative India), Brazil (Cena IV Shakespeare Cia), Ghana (Act for Change) and Scotland (the University of the West of Scotland).

Visitors browsing the site will see, in its Timeline of the Network’s growth and development, some South African roots! Henry Bell of UWS reviewed the Shakespeare ZA initiative #lockdownshakespeare for Shakespeare Bulletin – he had used the #lockdownshakespeare videos as a digital resource in his teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic, reflecting with students on how the project showcased locations, accents and languages through self-taping and site choice.

This led to the 2021 online event Lockdown Shakespeare: Transnational Explorations, co-hosted by the Tsikinya-Chaka Centre at Wits University and the Creative Media Academy at the University of the West of Scotland, at which an international mix of scholars and artists shared ideas about site-based Shakespeares and digital practice. Enter creative producer Ben Crystal, who approached Bell and his UWS colleague Steve Collins “to establish a network that could share methods and practice with each other”.

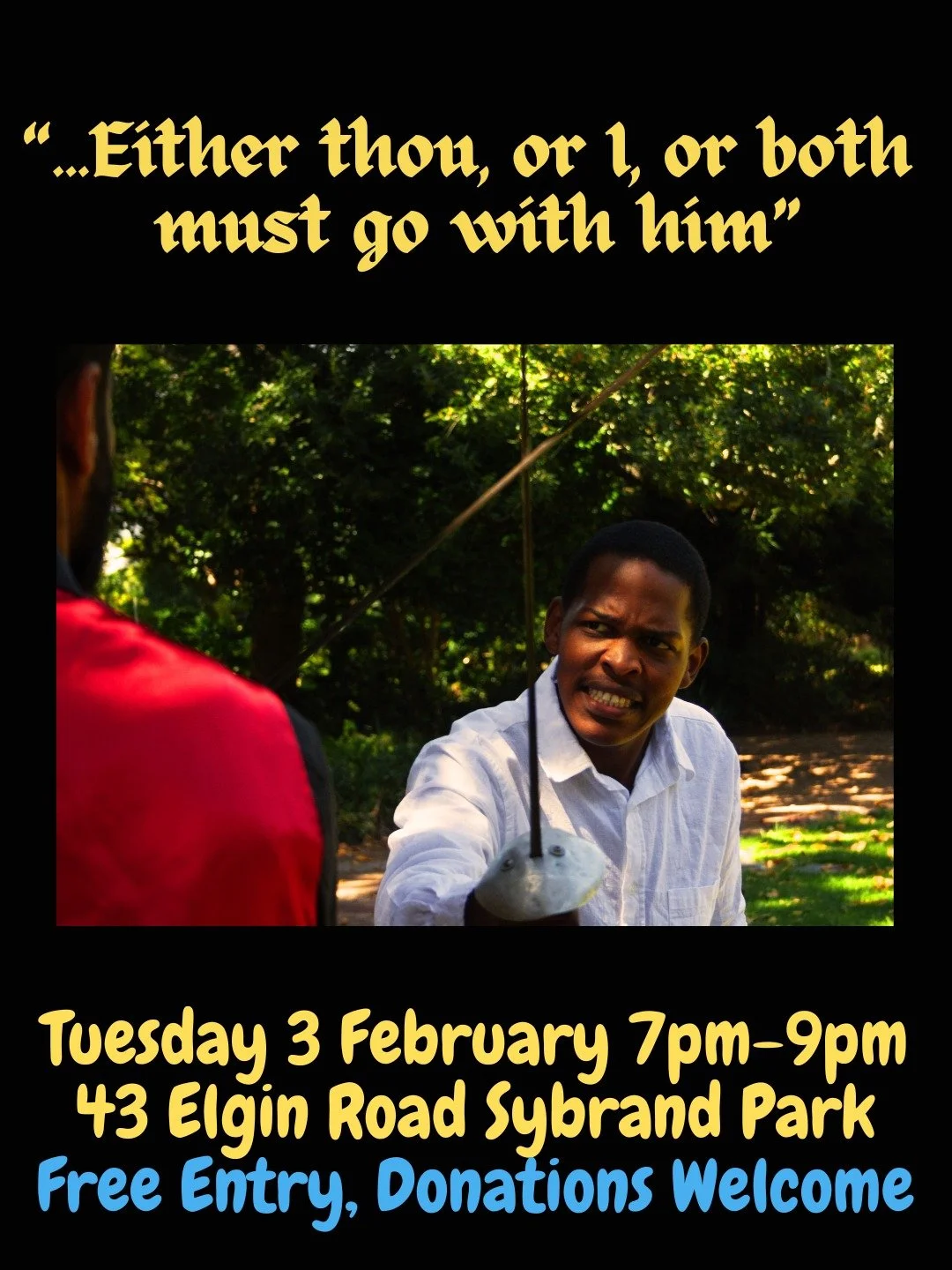

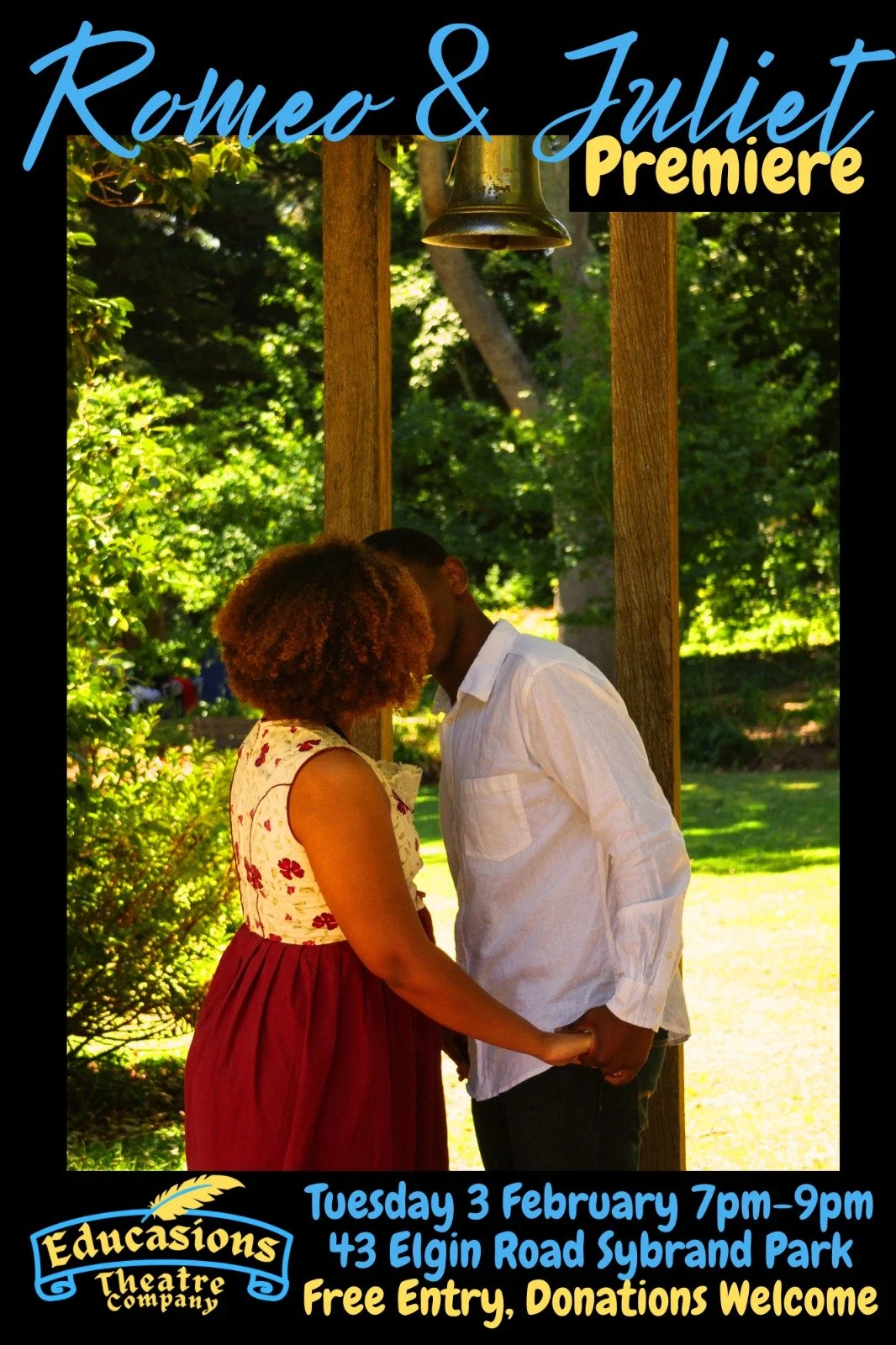

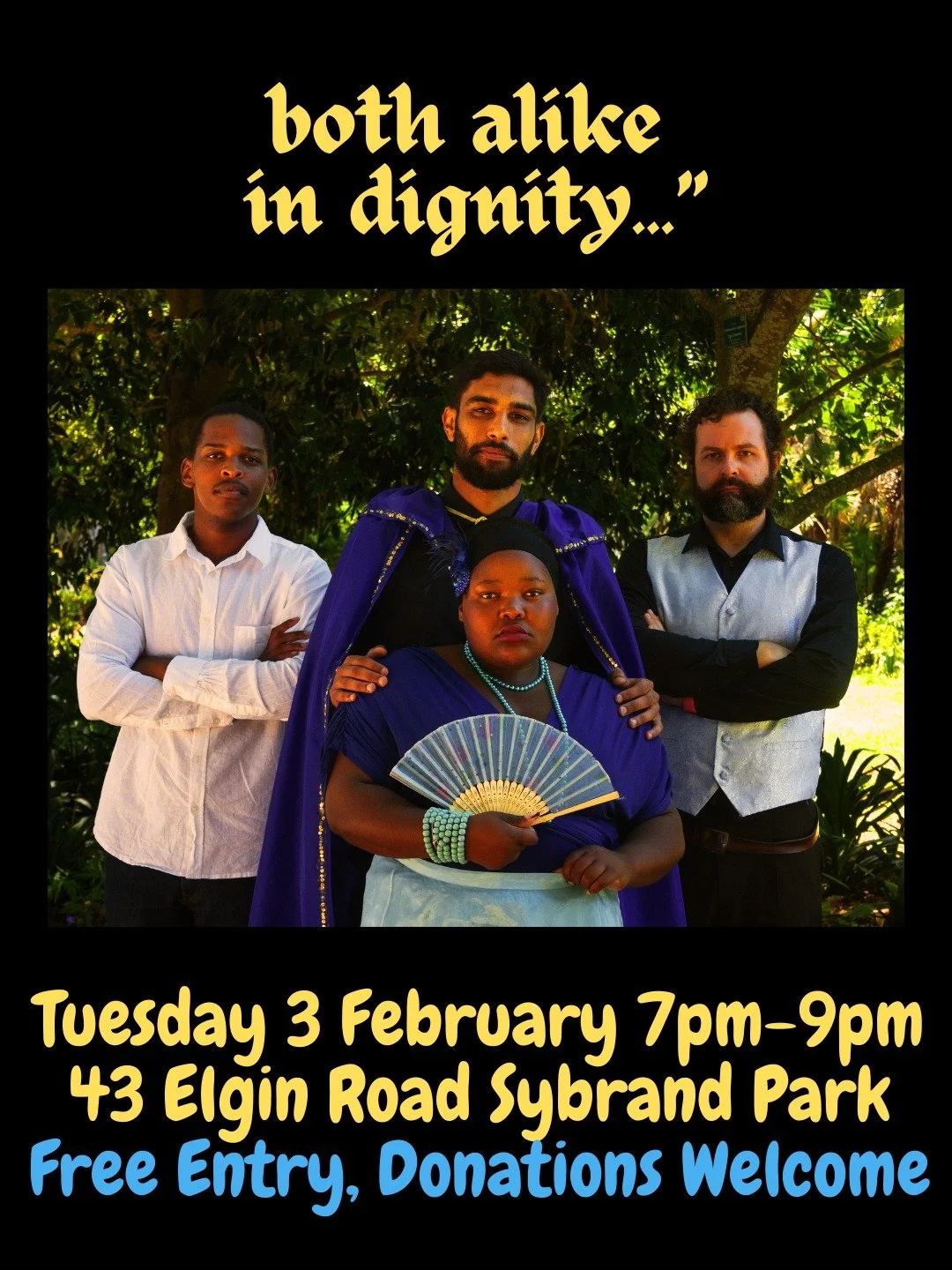

Artists from Act for Change, BraveSpaces Creative India and Cena IV Shakespeare Cia were invited to film short extracts from Othello, Romeo and Juliet and Measure For Measure in Accra, Mumbai and Sao Paolo respectively, placing an emphasis on the processes behind these digital creations. “A nascent method was formed out of a decentred collaborative approach”, driven by the practice of performing artists from the global south: “This methodology was then applied to teaching at UWS that saw films created by BA Performance students in Scottish English inspired by the work created in Brazil, Ghana and India.”